I Stood Up for My Kid When He Couldn’t Read, Now I Help Other Parents Do the Same

Advocating for your own kid, or teaching other people—doctors, dentists, teachers, etc.—about your kid, is something you learn as you go along. Even if you don’t work with any single barrier for long, your overall advocacy skills build with experience.

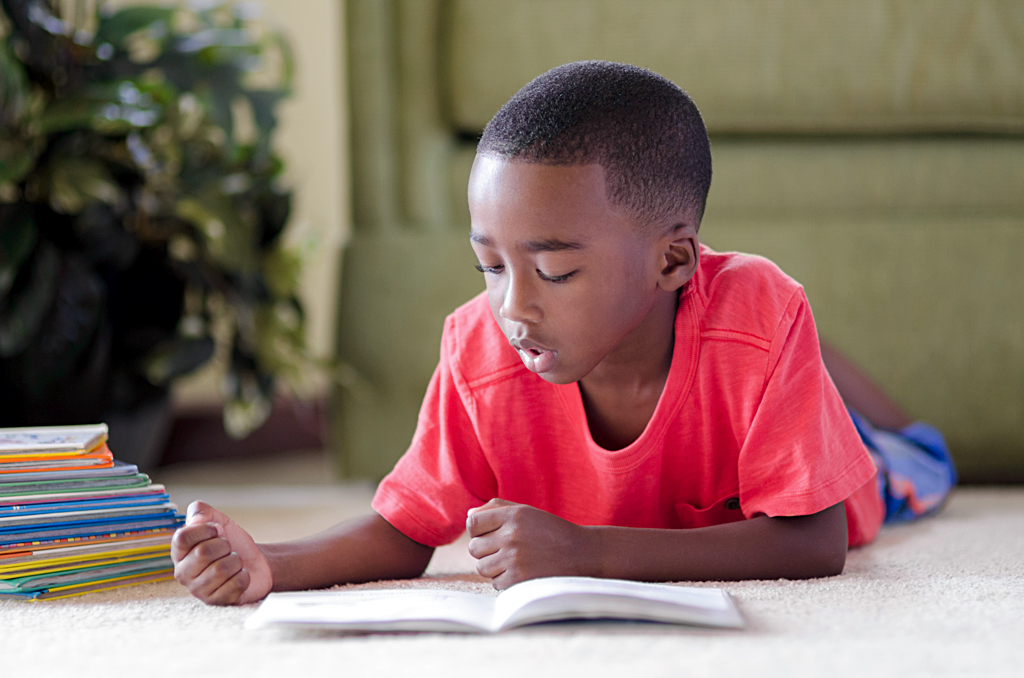

I learned this the hard way. I successfully advocated for my illiterate, suicidal fourth-grader to get a free and appropriate education at a school specializing in proper instruction for dyslexic kids and struggling readers. I also advocated for my mother, suffering from frontotemporal dementia, to get appropriate care at an assisted living facility.

In both cases, I was quick to understand that the powers-that-be thought they knew more and had more power than me. I gained confidence and balanced the scales by learning more, so I could approach conversations from a place of knowledge. I didn’t have to get a teaching degree or a psychology degree, but I had to learn what my son and mother needed, and understand why they weren’t getting it.

I came to this work with certain advantages. I have a college degree; I have had to research and learn new things for a living using physical libraries and resources and, of course, I have access to the internet, which can be a fantastic resource or a complete rabbit hole. To check my facts, I’ve had to interview people for information. Our family also had the financial resources and know-how to pay for private supports, from tutors, to camp, to lawyers.

Talking with my social network helped, too. By relying on thoughtful friends, I was introduced to another mother who had successfully gotten her kid into a school for dyslexic kids. She shared her process with me, and that gave me somewhere to start. Thanks to her, I knew specialized schools for kids with dyslexia existed. Could there be specialized summer programs, too? Specialized tutors? By talking with my sister in-law, a physician, who then consulted a friend, I got a list of neuropsychologists who could tell us more about our son.

I found Camp Dunnabeck online. I spoke on the phone with them about my son. We decided to visit and learn more. Not only did my son learn to read there, the camp helped me learn more about dyslexia and how to advocate for my son. I learned what he needed to continue his education.

One key to successful advocacy is having the confidence that you know your kid and being able to back up what you are saying with research. Increasing my own knowledge helped me level the playing field and fight for the education my child, and every child, is due.

Advocating for Other People’s Kids Requires an Intentional, Long-Term Campaign

Yet, after gaining all that knowledge, it took a whole new learning curve to take my advocacy to the next level: Not only advocating for my son, but for all children with dyslexia. I discovered that advocating for other people’s kids is much more intentional—a long term campaign.

I knew I had to start by learning even more. I attended sessions designed for parents of dyslexic kids about the best strategies to teach reading and writing. And I started researching on my own—reading books and meeting with experts to learn more about reading, language and dyslexia.

I began to ask bigger-picture questions. For example, one in every 60 kids are on the autism spectrum, which over the last decade has seen a significant uptick in public awareness and school attention. So how is it possible that at the same time, 1 of every 6 kids are dyslexic and yet so little is known about how to teach them?

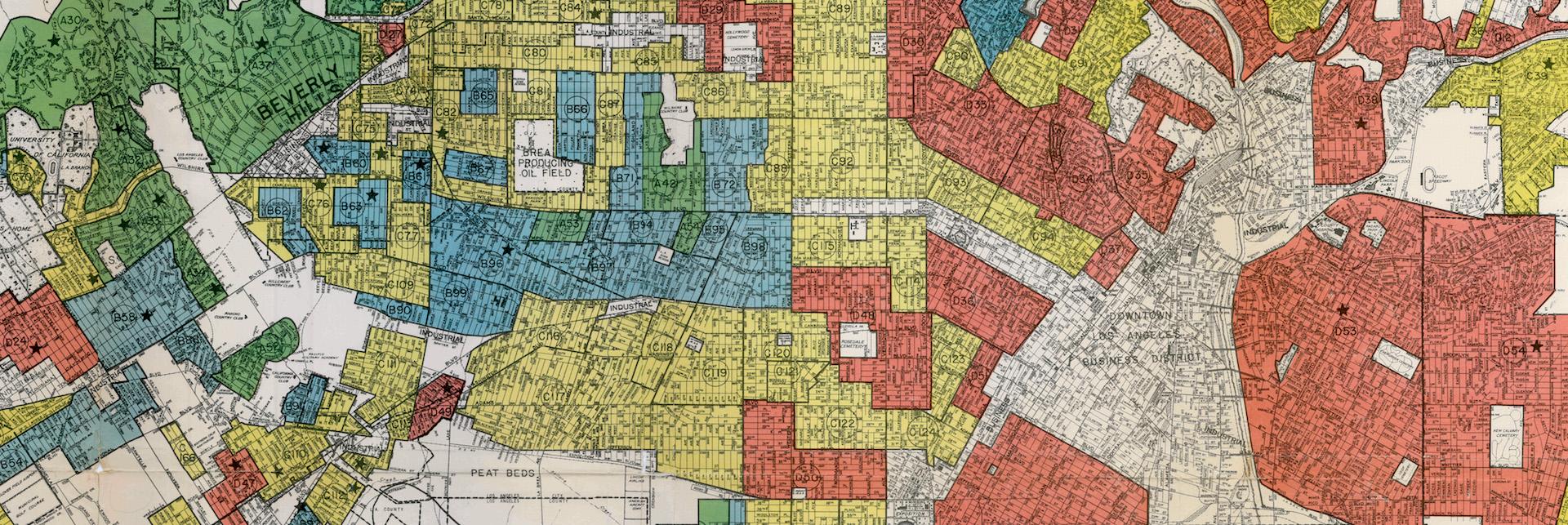

I found a lot of literature on poverty and illiteracy, but none correlating the illiteracy to ineffective instruction. I found a lot of information on school disconnectedness, illiteracy and school dropout rates, but again, nothing connecting this to instruction.

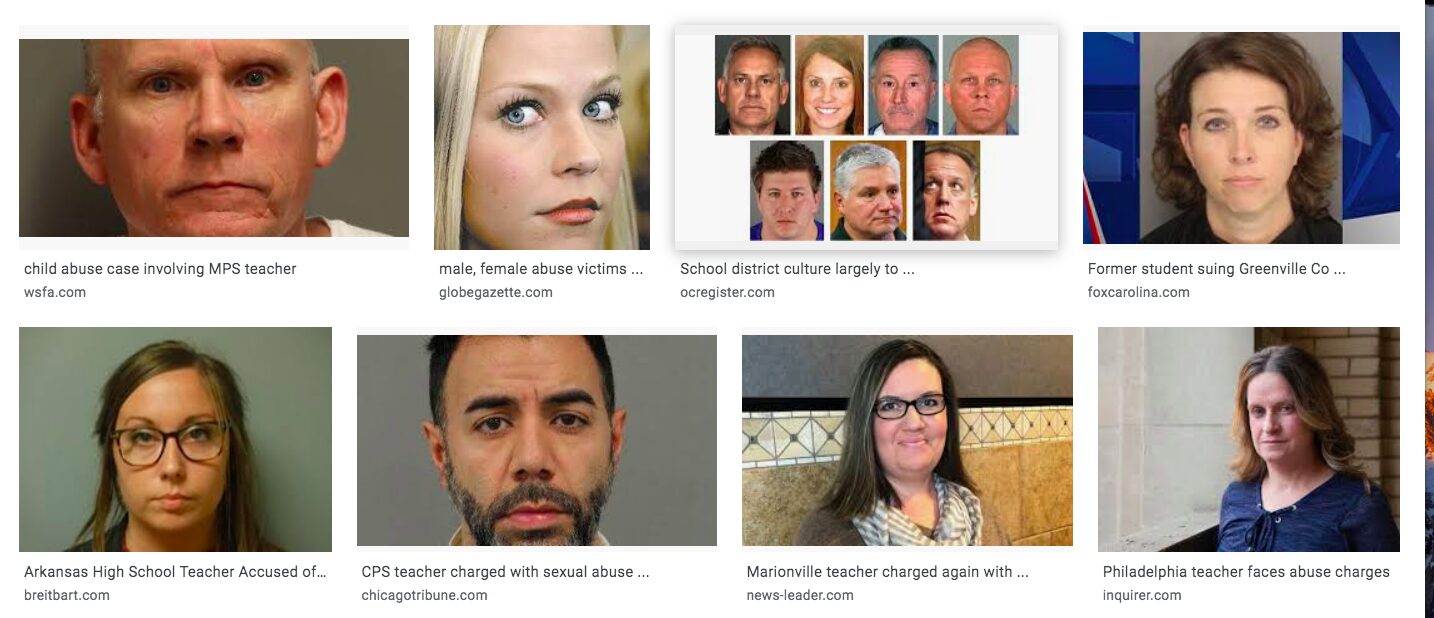

Because I was involved in ending mass incarceration, I researched the correlations between dyslexia, illiteracy and prison. It was clear—if you were not taught to read, you didn’t have many options. In the United States, about half of all prisoners are functionally illiterate due to dyslexia and poor instruction. I decided I wanted to look at this as an equity issue, and an instructional leadership and teacher preparation issue. How can teachers teach what they don’t know?

Friends were already calling me to see if I could help a parent from their kid’s school who was struggling. Their struggles have continued to keep me grounded.

Professionally, I had experience with advocacy at the federal level. As a volunteer, I had experience with local and state advocacy. My first step was to find out who is already advocating for kids in the dyslexia world. I didn’t imagine I was alone, and didn’t want to re-invent a wheel

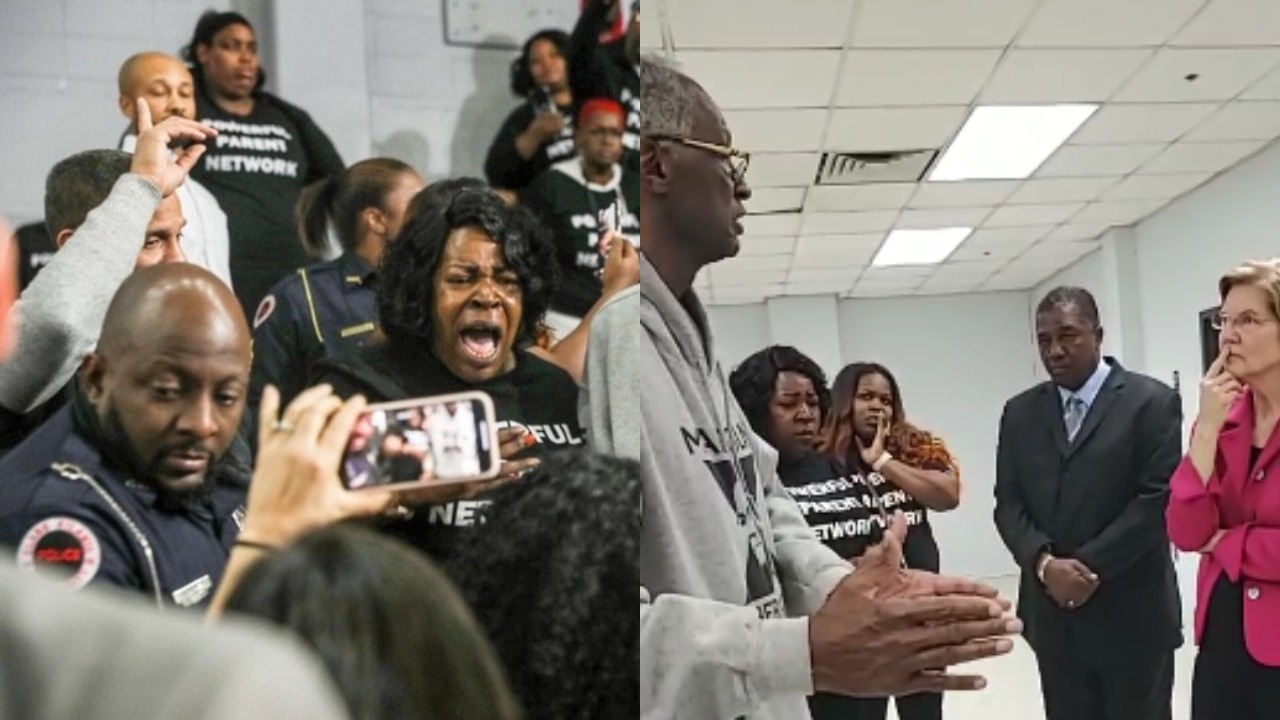

First, I found a dyslexia echo chamber on Facebook. I then connected with a friend who had worked in City Council, has a dyslexic son, and eventually we formed a task force and met with nearly every member of NYC Council. We joined the Arise Coalition of Advocates for Children. I went to the International Dyslexia Association Annual Conference. I found Decoding Dyslexia, looking at change through state laws, and I now lead the NYC Chapter. I found parents fighting their school or school district to get their children appropriate instruction, just as I had.

Learning to Teach Other Parents Never Ends

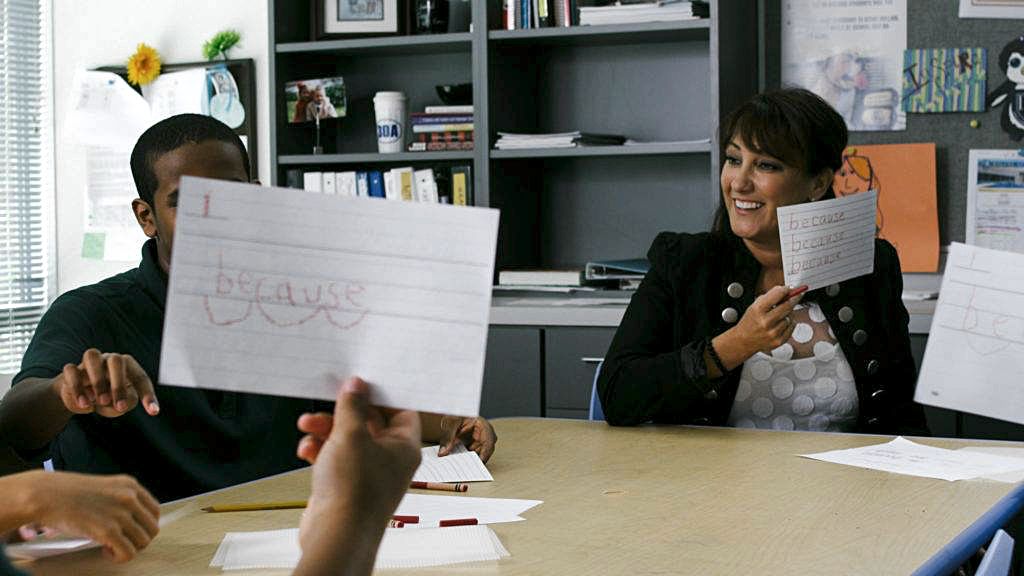

The “teaching” side of my advocacy work got started in 2015 when I was asked to present to New York District 5’s Harlem Diverse Learner conference. My first presentation for Harlem parents was clearly too long and too scientific.

Even so, afterwards, many parents approached me in tears because either they had had trouble learning to read or their children were struggling. At the time, sadly, I had little to offer. I’m not a lawyer. I knew just enough to get myself in trouble talking about the legal tools that help families get their kids into private, specialized school placements. All I could do was recommend they get tutoring and legal assistance.

Taking part in panels with other parents who have different experiences has been helpful. Parents with different experiences, whether because they are people of color, have more economic challenges or have personal experience with their own reading struggles as well as their children’s, can really hit home. I can support the work by sharing information and connecting their stories to wider audiences through writing.

When I began testifying at city and state hearings, knowing what other families had experienced allowed me to compare my family’s story to that of other families who didn’t have the time, flexibility and other resources we have been able to invest in fighting for our son’s education. Usually, other parents with those stories have also been present to share their direct experiences.

Over time, I’ve learned to make my presentations less technical and more resonant. I continue to speak on panels, organize events and testify to policymakers.

Even better, the advocacy work I do in concert with other parents is working. The New York City Department of Education is working to retrain teachers and school leaders in the science of reading. We must do better for students, so I continue to learn all I can to become a more effective advocate.