Teachers Can and Should Critique the Antiracism Ideology

“If you are going to show that, you need to discuss the ‘other side.’”

“What other side? We are studying the African American experience, not the other side,” I stated, feeling incredibly self-righteous. The parent on the phone was smart enough to realize the trap I had laid for her. She knew I was assuming she was racist, and she was right. I did assume this about her. She did not speak with me again.

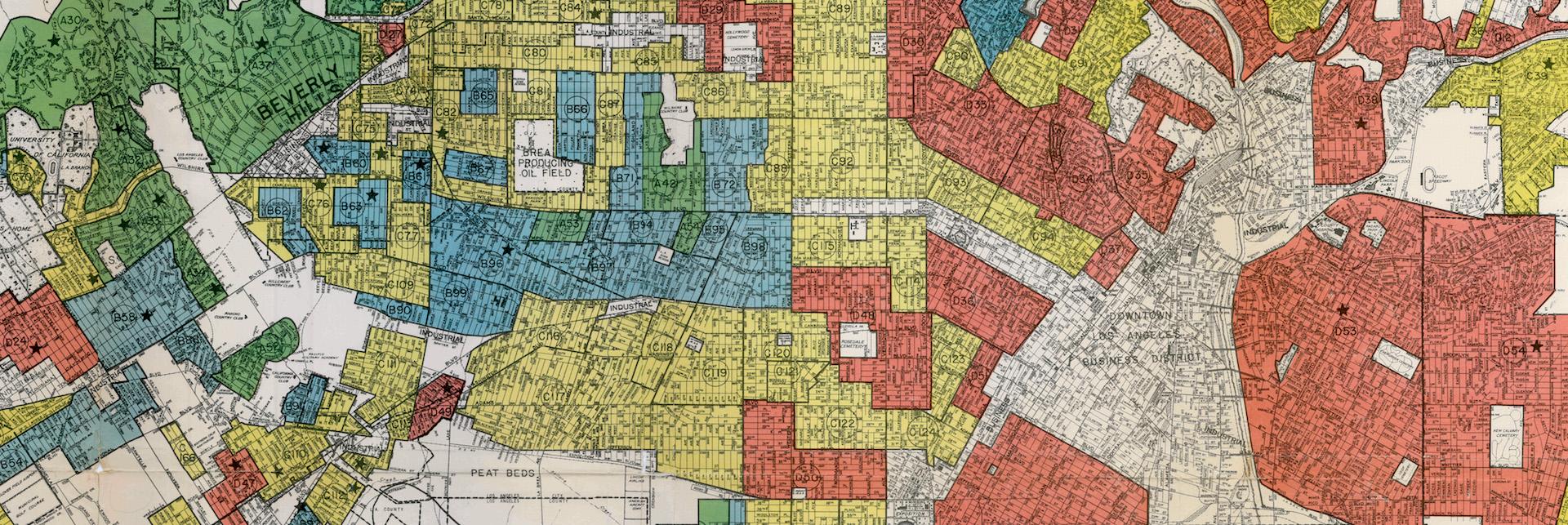

About four years ago, with some colleagues, we revamped a humanities course called The American Dream. In a linear fashion, we wanted to show the thread line of the African American experience. Our units looked thusly: We would teach Zora Neale Hurston’s “Their Eyes Were Watching God” and Reconstruction moving into ultimately the Harlem Renaissance. We would then teach “Raisin in the Sun,” by Lorraine Hansberry, as well as the civil rights movement and, especially, redlining. Finally, our last unit would be the novel, “The Other Wes Moore,” by Wes Moore, pairing it with contemporary presidential policy and focusing on the crack epidemic/mass incarceration. During our last unit, I showed the documentary, “13th,” with the intention of connecting it to our literature. A parent demanded I speak with her over the phone during my prep period, and she was quite angry at the “biased” documentary that I showed.

Like many teachers outraged and supportive of the Black Lives Matter movement following the death of Trayvon Martin, I subscribed to Teaching Tolerance, I watched the documentary, “13th,” multiple times, skimmed Ibram Kendi’s digestible paperbacks, listened to Nikole Hannah-Jones explain “The 1619 Project,” and the list continued. Since the murder of George Floyd, however, my outrage has cooled into skepticism. I no longer support this movement, and I am uncomfortable being part of a “viewpoint minority” within secondary education.

My discomfort stems from observing an insidious authoritarian pressure in many an institution to protect themselves from charges of racism, as the trendy new definition of racism—prejudice plus power—aggressively calls for revolutionary dismantling of institutional structures. Antiracism ideology is built on a specific premise: Racial disparities are the result of a white supremacist society. Therefore, it is incumbent upon all of us to locate this hidden, ambiguous systemic racism, whether that means creating more “diversity committees,” requiring employees to participate in Robin DiAngelo’s antiracism workshops, or even considering paying employees of color more money “for the invisible work they do” and pushing for more Black faculty representation, as was seen at Princeton University. A professor, Sergiu Klainerman, gave an appropriately exasperated response:

In my own department, Mathematics, both the faculty and graduate students are recruited from all over the world with absolutely no regard for any other criteria beyond excellence in research, scholarship, and teaching. If anything, the process produces a shockingly small number of US-born faculty—at my counting less than 15 percent. Our department has for years been credited as the top Mathematics department in the US and probably in the world. I very much doubt that we could maintain that position if we introduced a quota policy for US citizens to counter their lack of proportional representation in our program…The wild accusation of structural racism and anti-Blackness appears to be based only on the statistical under-representation of African Americans at Princeton. The statistics are true, but I strongly dispute that they have anything to do with racism.

Within our elementary and secondary schools, perhaps we should, like Klainerman, refrain from labeling horrific events, as well as racial disparities, as “systemic racism,” especially in our classrooms where our words carry an authoritative weight. Even the topic of police brutality contains some particular nuances that seem to be missing from a movement that claims we should be having more dialogue. Coleman Hughes—whose work has been seen in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and other publications—lists a series of white men who were killed by the police in equally horrific ways to their Black counterparts. Here is an excerpt from “Stories and Data,” published in City Journal:

For every Black person killed by the police, there is at least one white person (usually many) killed in a similar way. The day before cops in Louisville barged into Breonna Taylor’s home and killed her, cops barged into the home of a white man named Duncan Lemp, killed him, and wounded his girlfriend (who was sleeping beside him). Even George Floyd, whose death was particularly brutal, has a white counterpart: Tony Timpa. Timpa was killed in 2016 by a Dallas police officer who used his knee to pin Timpa to the ground (face down) for 13 minutes. In the video, you can hear Timpa whimpering and begging to be let go. After he lets out his final breaths, the officers begin cracking jokes about him. Criminal charges initially brought against them were later dropped.

Hughes selects a random year (2015) and lists white people who have been killed by the police. He argues that police reform should happen; however, it is not good journalism to assume that the police are systematically racist in 2020. It is also not good teaching if we verbalize our assumptions in class.

This kind of careful journalism by Hughes is necessary for us to read as educators because claims that schools criminalize students of color cause panic and create more costly bureaucracy. I’m a high school English teacher, and I’m seeing a push to implement a very specific ideology in my classroom, and to be fair, this push has been happening for years; however, the events of the summer coupled with the pandemic and an incompetent president have created quite the cocktail. Here are some critiques I have regarding the antiracism ideology, and I’m hoping that readers will not make the grand assumption that I’m a racist, as this kind of ad hominem attack popular on Twitter is not fitting for our field.

- Kendi and DiAngelo consistently employ an either/or logical fallacy. “If you are not actively fighting racism, you are condoning it,” so the ideology posits. People don’t want to be labeled as racist; it is an incredible insult. However, if someone wants to discuss antiracist ideology without fully supporting it, that person is considered not only uneducated, but racist. We have to take this logical fallacy seriously. The fear of this label will stunt speech in the classroom. All ideas need to be subject to critique and questioning; this ideology protects itself from that kind of rigorous scrutiny with a strange authoritarian threat. Classrooms cannot be “safe spaces” for ideas.

- Well intentioned educators lack understanding in this ideology’s origins. Antiracism ideology is stemming from a kind of revised postmodernist philosophy (and from that, Critical Race Theory). Postmodernists argue that there is no such thing as objective truth—truth is merely a narrative held by the groups who hold the power in society. While postmodernism is a great literary lens in which to discuss different historical narratives, I am hoping that educators can see that this also brings with it dangerous consequences. By denying objective truth, we are now going to deny the scientific method. Antiracism has many similarities to religion in this way. John McWhorter—linguistics professor at Columbia University and contributing writer to The Atlantic—compares this kind of constant “admission to white privilege” to a Catholic going to confession (and consequently, feeling better having “repented”). Not only this, all white people must acknowledge that all narratives by people of color are “true.” (This bares a striking resemblance to the mantra “believe all women” from the problematic #MeToo movement.) Questioning these narratives becomes a form of “epistemic injustice.” By asking for evidence, whites are committing acts of racism. For more information regarding the roots of Critical Race Theory, read James Lindsay and Helen Pluckrose’s book, “Cynical Theories.”

- Antiracism considers critical thinking, logic, and science to be “white.” When I read “White Fragility,” I was struck by how many historical stereotypes were being used to categorize racial identity. Actually, DiAngelo often conflates race with culture, yet wants to make everything about race specifically, and thinks that colorblindness is a dangerous goal. I found it especially alarming that she labels science, logic, and critical thinking as “a white form of knowledge.” I wonder if she fully grasps the importance of the Enlightenment and the American ideals borne from it. Yes, America has a long history with racism, but we cannot simply dismantle Enlightenment ideals when those are what bind us together across a diverse people. Science, logic, and critical thinking cannot be seen as merely white endeavors. In fact, I find it horribly insulting to people of color to even suggest that because of their race or culture, they aren’t “made” for science. This racist idea does not help any human achieve their full potential.

- Students are learning some regressive, racist ideas. Like a hawk, I have been observing an activist social media webpage created by students in my school who are truly concerned, loving, and desirous to “be the change.” Similar to their teachers, they are ingesting this ideology. I’m not sure this is to our society’s benefit. Following DiAngelo’s lead (whether they knew it or not), students claimed that “we can’t be so concerned by start times/bells because Black kids can’t get to school on time.” I cringed at the earnestness of this kind of “caring.” I can’t help but think of McWhorter’s last paragraph in his book review:

White Fragility is, in the end, a book about how to make certain educated white readers feel better about themselves. DiAngelo’s outlook rests upon a depiction of Black people as endlessly delicate poster children within this self-gratifying fantasy about how white America needs to think—or, better, stop thinking. Her answer to white fragility, in other words, entails an elaborate and pitilessly dehumanizing condescension toward Black people. The sad truth is that anyone falling under the sway of this blinkered, self-satisfied, punitive stunt of a primer has been taught, by a well-intentioned but tragically misguided pastor, how to be racist in a whole new way.

This list of critiques brings me to particularly egregious anti-intellectual work now encouraged in secondary and primary education. An example is a provocatively titled article, “White Teachers, Our Whiteness Is Getting in Our Way.” The author ironically wishes for better antiracist articles for educators to “move the conversation forward.” He lists some tropes seen in this particular brand of educational journalism, and then he seems to seek deeper admissions from white teacher leaders (the Teacher of the Year program, to be exact) when they have been racist. Following the postmodernist philosophy, he uses narratives to emphasize “systemic racism” in the educational system. Some teacher leaders didn’t open up as deeply as he wanted. He desires a rather specific kind of “vulnerability.” I agree that we should model introspection in the classroom; however, his confessional moments aren’t the only stories or perspectives worth exploring.

I believe that I was anti-intellectual when I thought that a parent searching for multiple perspectives was racist. I was anti-intellectual when I believed that equity is a worthy goal, despite historical tragedies clearly displaying that it is not. I was anti-intellectual when I did not read Harvard economist Roland Fryer’s “Empirical Analysis of Racial Differences in Police Use of Force,” before showing what, yes, is a biased documentary. Instead of a teacher, I was an activist. If a parent claimed that I was indoctrinating students at that moment, today, I would concede to this accusation.

We have to separate intellectualism from activism. The Teacher of the Year program has a specific political agenda, and we absolutely can question this agenda. If we are in the business of education, then let’s make critical thinking a priority. Let’s put all ideas on the table instead of representing companies, tribes, and the Department of Education. We have to hold true to Enlightenment ideals: freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom of the press, etc. We have to respect the individual. As teachers, let’s not be so narrow-minded to think we are just the protectors of children; we must also be the protectors of people who seek truth, even if it isn’t politically correct.

Challenging a narrative is not racist. Let’s be more thoughtful with our language. Let’s be good Enlightenment thinkers and teach our students to question everything with an open mind.