Literacy: The Forgotten Social Justice Issue

My grandfather was in his late 30s when he first learned to read and later went on to complete his GED at the age of 42. With his formal education ending around age nine so he could start working, and during a time when if caught reading he would be attacked, threatened, or possibly murdered for daring to be a Black man reading in the Jim Crow south, he took the risk and taught himself to read using the bible.

I tell this story not to celebrate the strength of my family, but to paint a picture of how woefully detached the debate over basic literacy is from the desires of families. Just two generations ago people risked their lives to be able to read and here we are today watching the educational establishment—through its degradation of standardised assessments, emphasis on the individual over the collective whole, and dismissal of science – risk the subjugation of an entire people to second class citizenship. It is frightening and marks the gravest miscarriage of justice we have seen this side of educational history. An entire generation of children is not being taught to read.

No Expectations, No Problem

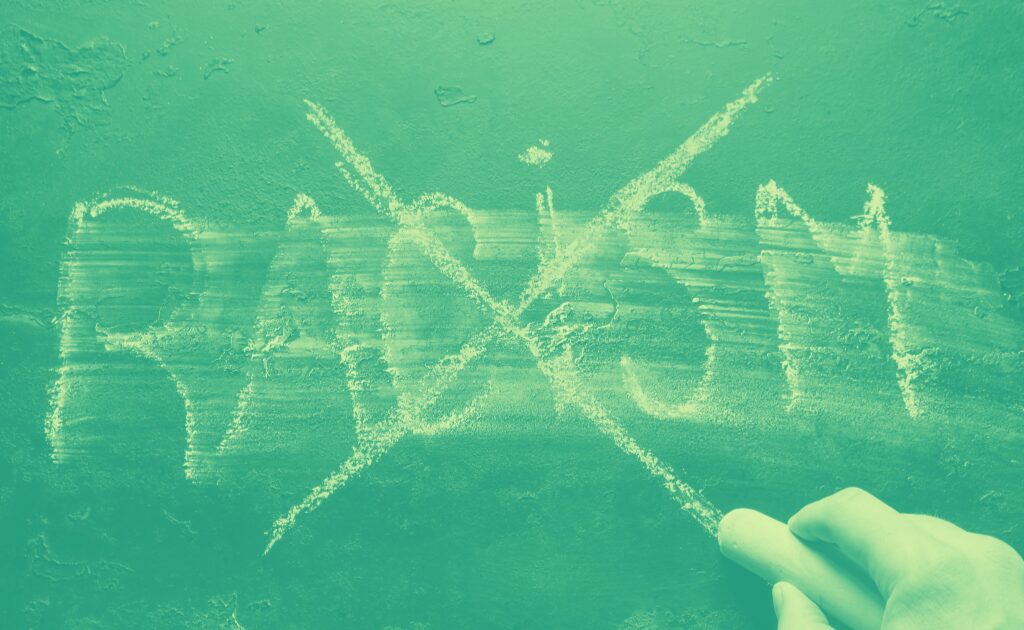

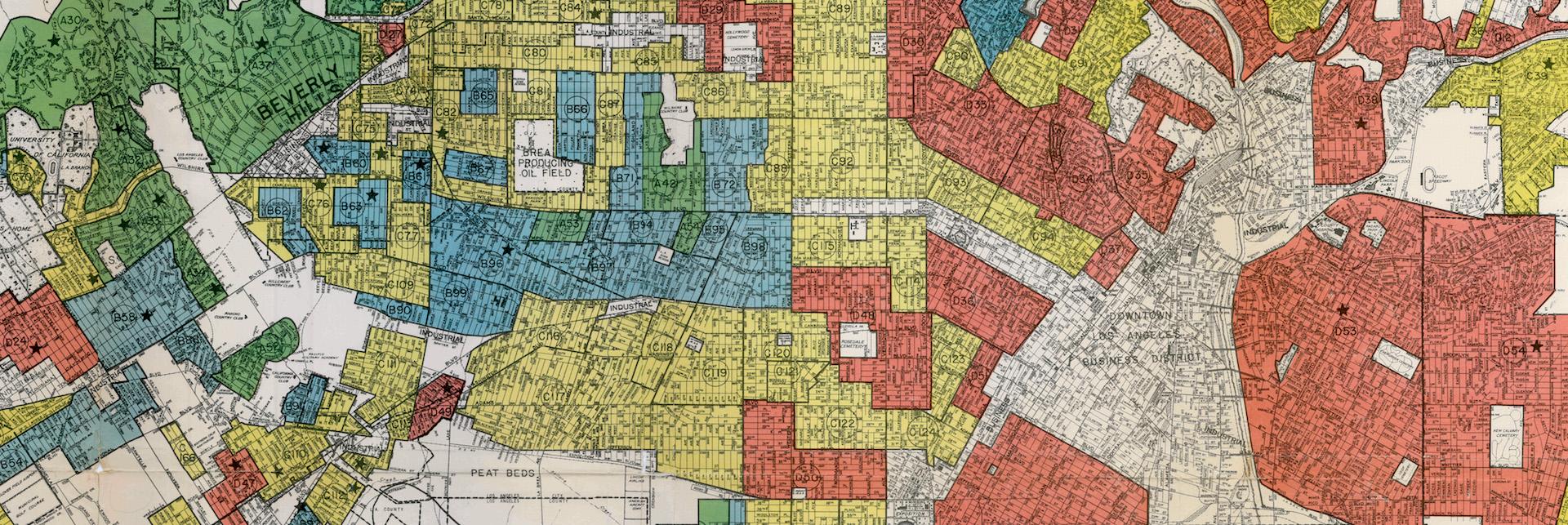

In 2017, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) found that sixty percent of children nationwide are not reading proficiently. If we look to the disaggregated data by race, it becomes even more stark. Though these levels of proficiency have not improved in the last 30 years, we’ve been made to believe that tests don’t matter. That tests are racist and cannot accurately measure what our students know. We can call tests racist (the people making them might be), and inaccurate measures of achievement (they actually measure general knowledge), but overall, what has this amounted to? A lowering of expectations across the board.

A school can earn a designation of *high-performing with just 60% of its students on grade level. This means that 40% of the school is not reading and comprehending texts proficiently. Which 40% of our children don’t deserve to read?

A public school in my neighborhood has approximately 34% of students meeting or exceeding standards in reading, yet is categorized as “changing the odds” for African-American students. 70% of Black children in this school are still struggling to read, but this is the best choice that parents have for instruction in the area.

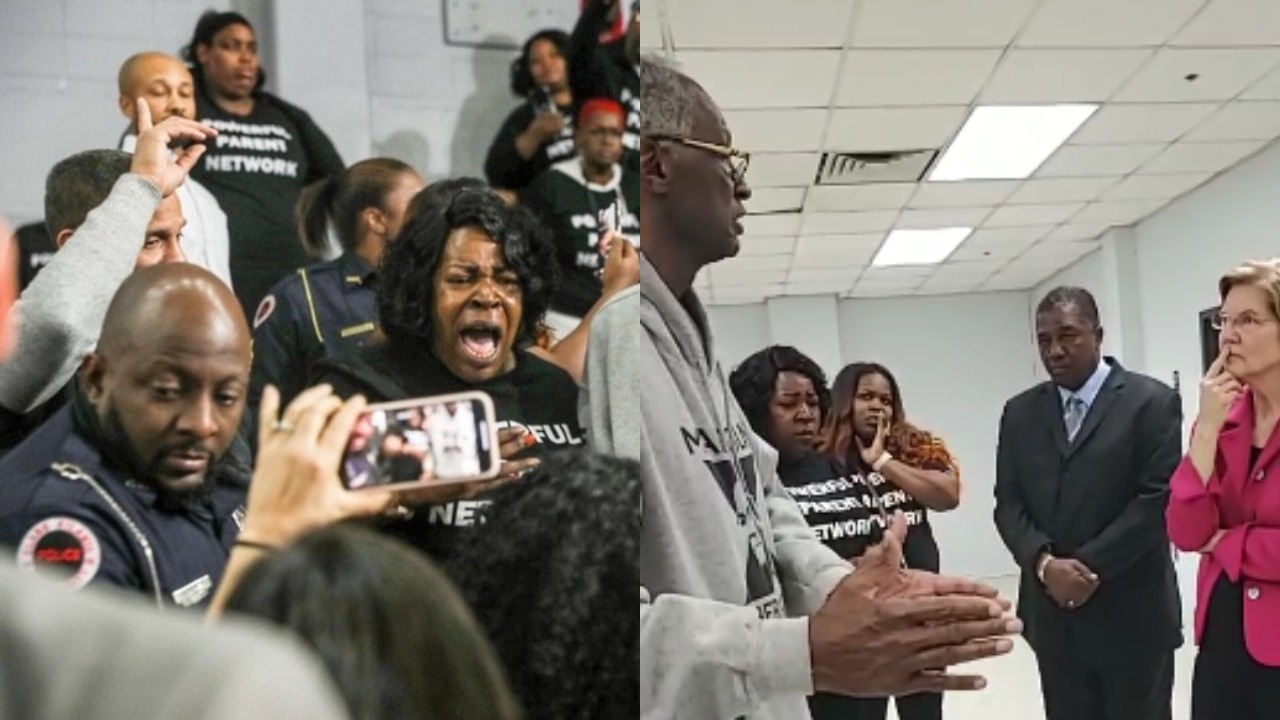

We cannot place our individual notions of what progress and performance looks like on a community that we do not know. Before deciding for our students that tests don’t matter, a proclamation that comes from the privilege of never having had to worry about the implications of tests on our lives, in all things, we must partner with parents and ask: Do they care that their child isn’t reading on grade level? Do they care that faulty theories are being used in their child’s classroom?

For the families that I’ve worked with during my short time in education thus far, the answer is a resounding “yes”.

How We Read is Settled Science: Let’s Use It

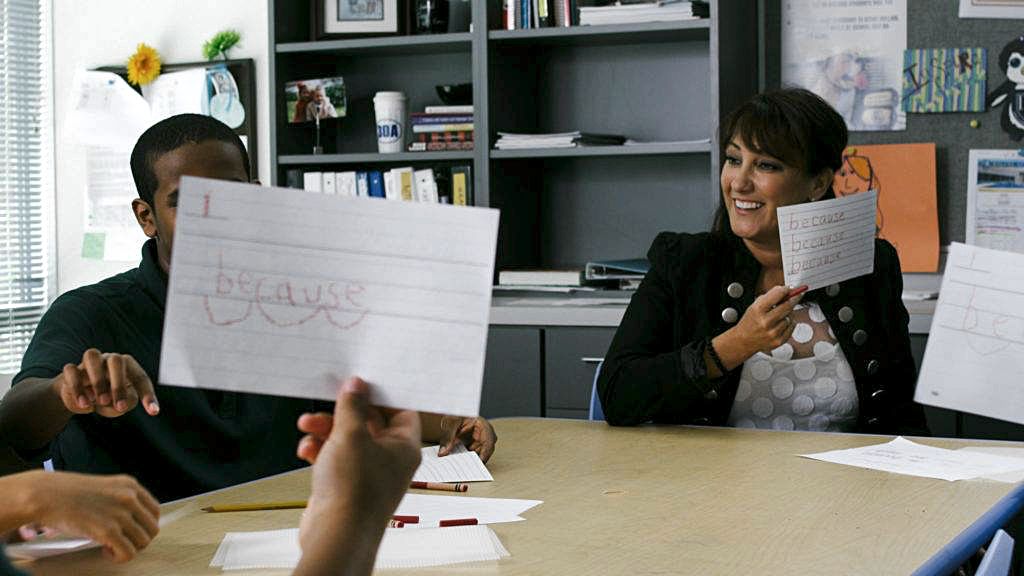

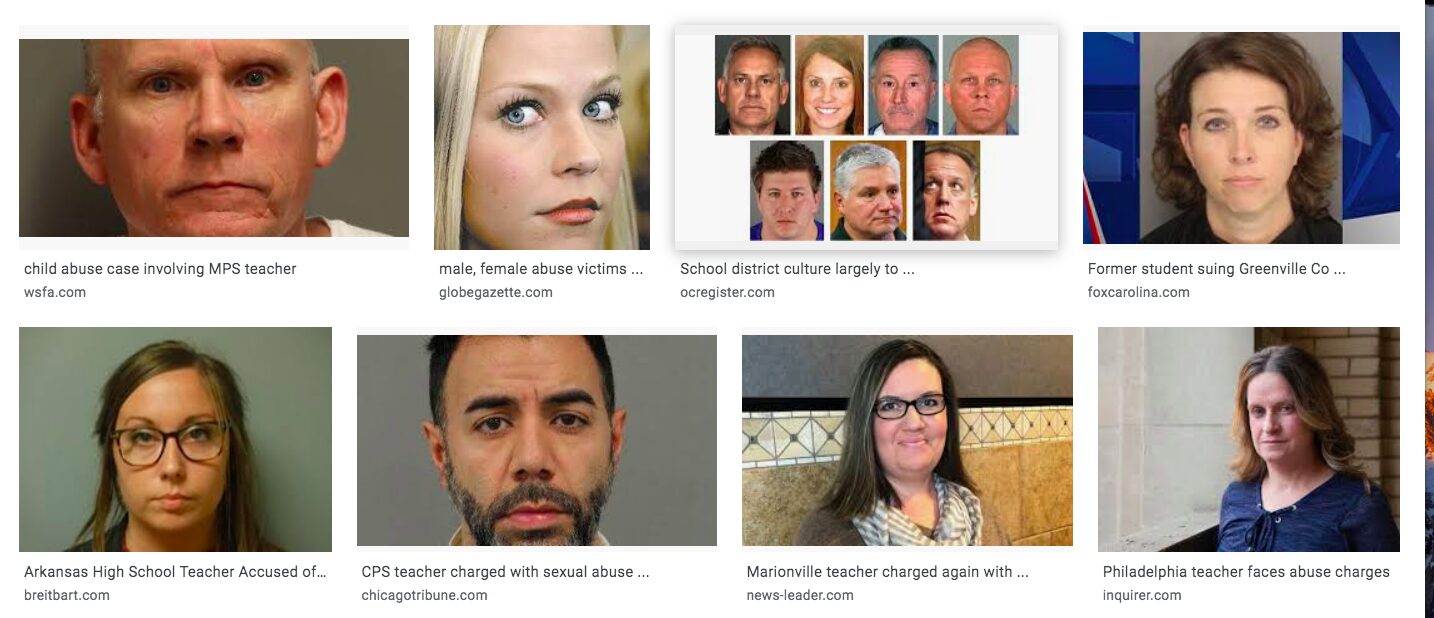

The National Reading Panel was convened by Congress in 1999 to determine the most effective method of teaching children to read. The panel, comprised of 14 reading experts, reviewed more than 100,000 studies on how children learn to read and concluded that students need explicit instruction in “The Big 5” of reading, phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension, and that teacher education programs needed to train teachers in these methods.

Despite the overwhelming evidence published by the panel, less than 40% of elementary education programs nationwide have adopted the teaching of all five components of reading in their methods courses since then, and as a result, millions of children are still being taught to read with a flawed theory of reading. Schools have been allowed to fail our children without consequence, and more money for schools won’t solve the literacy crisis when the fundamental issue is that we aren’t being prepared to do our jobs. We must raise our bar. We can no longer be complacent and accept mediocrity as evidence of change. We must be the ones to demand evidence in our classrooms.

So, while the traditional model of social justice educator has become a rallying cry of “Black Lives Matter” with a performative poster in a classroom, I take a different lens. I am a social justice educator with roots in the history of my grandparents, in the history of my community who has been failed by shoddy science in the name of a “progressive” education. Yes, Black lives matter. But in the context of schools, as educators, as people who claim that their life’s work is for Black, brown, and disenfranchised children, we can not fully proclaim that Black Lives Matter until Black literacy does.

Black lives matter in schools when Black grades, scores, and academic outcomes do.

*I compared data of high-performing schools from Minneapolis School Finder to the Minnesota Report Card. Many of the high-performing schools had a reading proficiency of 50-60%.