If You’re a True Expert in the Classroom, You Know COVID Learning Loss Is Nothing New

In addition to the usual conversations that mark the beginning of the new school year, this year we’ve seen a lot of conversation about student learning loss that has happened during the pandemic. The powers that be have begun to move on from learning loss to what to sell do about it. It may be tempting to be swayed by Accelerate Learning! edu salesmen, but we must remember: No one knows what it has been like to teach the past two years except those who have done so.

We should approach this year not with the snake oil rebranded acceleration stamps, but with the knowledge that the concept of learning loss is nothing new.

I have never taught or worked in a school where the majority of students read at grade level, and I routinely teach kids who are below where I want them to be. There have always been those who have worked to bridge those gaps, so we should approach this year not with the snake oil rebranded acceleration stamps, but with the knowledge that the concept of learning loss is nothing new.

Nationwide, less than 40% of children read on grade level by the time they graduate, and this number has largely not moved since the NAEP began collecting data in the 90s. As such, COVID-19 or not, many students arrive in secondary school with varying levels of background knowledge and fluency in simply being able to read the words on the page.

Teaching English coherently is a feat in and of itself. Notwithstanding that literature can already feel like an intangible and elusive subject with its lack of a centralized body of knowledge like chemistry or maths, (not to mention the ever-present teenage apathy). It follows that the path of least resistance would be to allow students to choose the books they want, to opt for immediately engaging books at their level, but English — and school — is about much more than simply doing what we like.

We have to reconcile the imperative to create safe and affirming spaces with a pedagogical approach that closes the gaps with which they will inevitably come.

There are students who enjoy my classes of explicit instruction in whole-class novels — where we all read the same novel and the teacher guides students through it. And then there are students who enjoy the choice novel centered classrooms — where everyone reads their own text and the teacher is on the sidelines. But I don’t believe that students enjoy our classes because of the books we do or don’t teach, but rather because we see them as full human beings in our classroom. As a profession, we have to reconcile the imperative to create safe and affirming spaces with a pedagogical approach that closes the gaps with which they will inevitably come.

Even though students may enjoy choosing their own books, and reading for pleasure is a net good into our lives, reading for pleasure is not the same as studying a field of knowledge, just as we don’t study math to instill a love of math. Before making rash decisions or claiming that a teacher-led approach only works “for some students,” we need to ask ourselves what opportunities we are implicitly denying when letting the kids run the room.

When students never read anything other than what is entertaining, immediately interesting, or even lexically simplistic such as many popular Young Adult novels, we deny them the opportunity to grow as sophisticated and complex readers.

When students never read anything other than what is entertaining, immediately interesting, or even lexically simplistic (such as many popular Young Adult novels) we deny them the opportunity to grow as sophisticated and complex readers. Students will not become better readers by magic, and as English teacher Andy Tharby tells us in his book “Making Every English Lesson Count,” it’s our job to model with ‘precision and clarity.’ Literacy instruction doesn’t stop once kids have learned to decode.

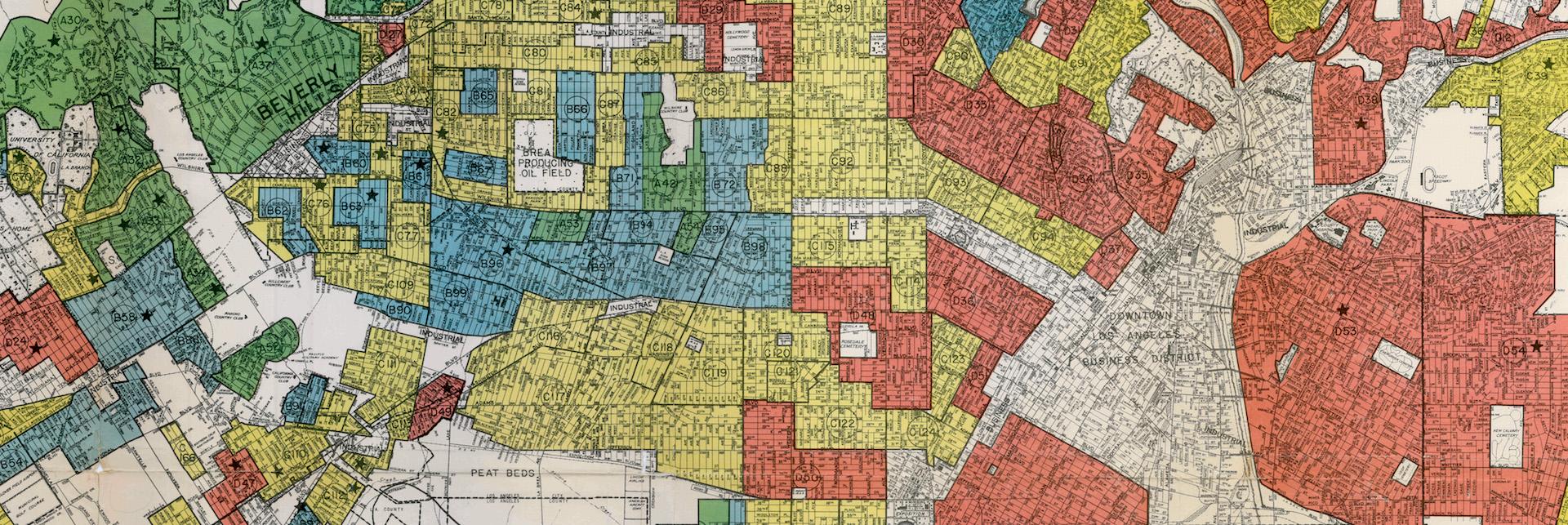

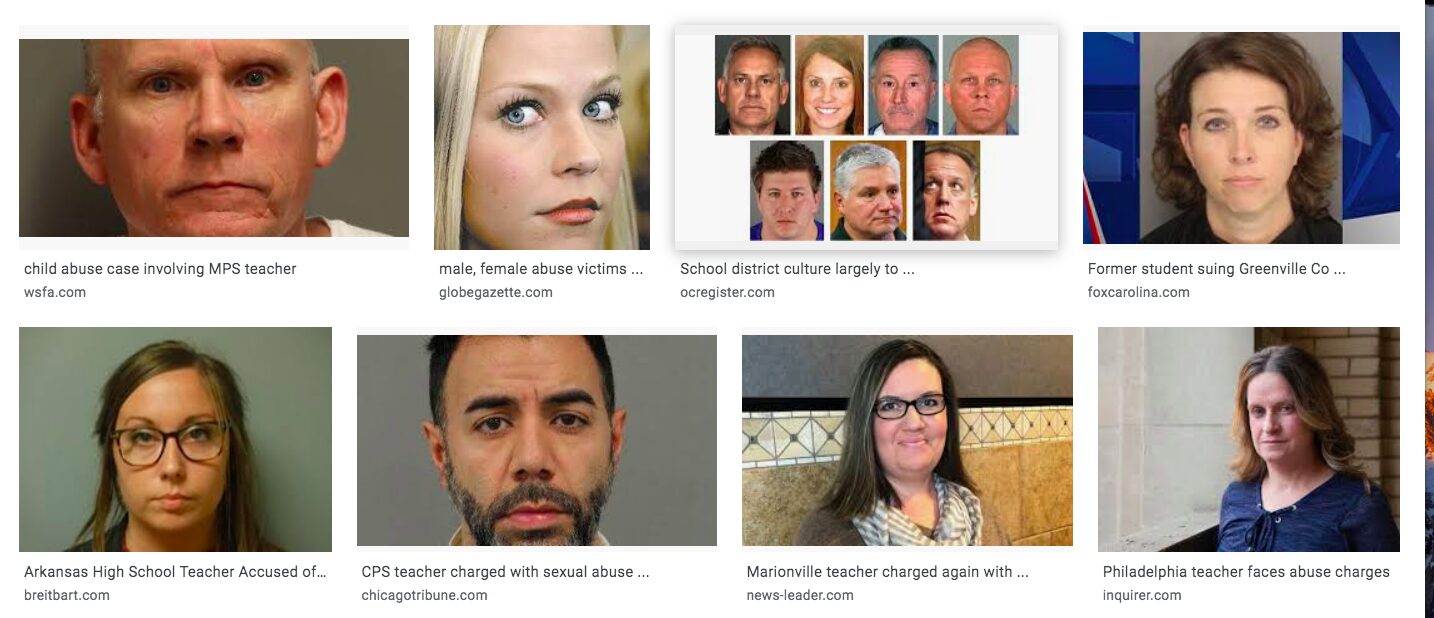

We can claim that the standards created were racist, that they attempt to curtail creativity or push students into a box — and this may be true. But do we reduce literature from an academic field of study to book clubs centered around what students are interested in? Or do we disrupt the genre by teaching “other literacies” when we haven’t even gotten basic literacy sorted first? I say no. We need to prepare students to be able to navigate the world that exists, while teaching them tools that enable them to actively change things for themselves in the future.

We should listen to the effective instructional and chalkface teachers who have bridged the academic skills gaps for students before, rather than those whose existence is predicated on being as far away from the classroom as possible.

Grades matter, tests matter, and they will for the foreseeable future. Whether kids like our class cannot be our measure of academic efficacy. We should listen to the effective instructional and chalkface teachers who have bridged the academic skills gaps for students before, rather than those whose existence is predicated on being as far away from the classroom as possible.

Instead of looking at this year’s academic challenges as something completely unfounded and never before seen, we could instead build upon what effective classroom teachers have always done and be the expert in the room.