Lucy, We Told You So

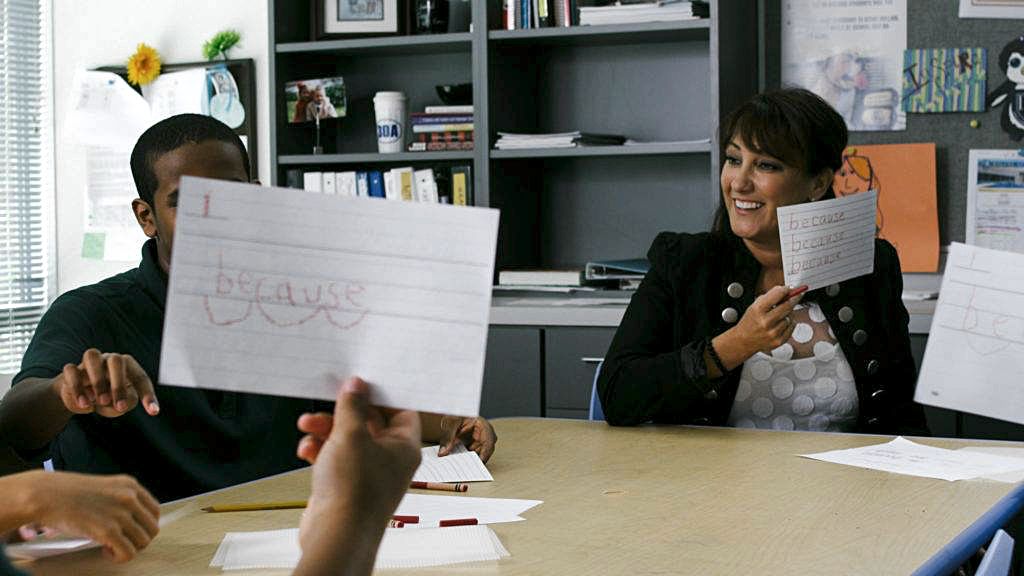

“Pouring over the work of contemporary reading researchers has led us to believe that aspects of balanced literacy need some ‘rebalancing.’”

Those words, written by the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project and made public thanks to the terrific reporting of Emily Hanford and APM Reports, may indeed be the educational understatement of the year. Or of the decade.

For those who have not been in the trenches of the Reading Wars the past few decades or so, those words may have little meaning. But to read them from Lucy Calkins is to hear the reading emperor herself declare that she has no clothes.

For far too long, the Reading and Writing Project has been used as the crown jewel of the “whole language” empire. According to RAND, one in five U.S. elementary schools used Lucy Calkins materials during the last school year. It is the third-most used core reading program in the United States. School districts across the nation fall over themselves to write big checks to train their elementary school teachers in the Lucy Calkins way, believing that indoctrinating their educators onto the path of Calkins’ whole language approach was the secret to school success. And that the Columbia University Teachers College seal all but assured it was research based and proven effective.

While advocates like Calkins have rebranded their work as “balanced literary” in recent years, there has been very little balanced about it. Twenty years ago, the National Reading Panel issued a ground-breaking study – Teaching Children to Read – which detailed the findings of decades of high-quality research determining what the science says is most effective in teaching literacy. The National Reading Panel emphasized that good reading instruction incorporates explicit and systematic instruction in five components of reading:

- Phonemic awareness: the ability to hear, identify and play with individual sounds — or phonemes — in spoken words

- Phonics: an understanding that there is a relationship between the letters of written language and the sounds of spoken language

- Fluency: the capacity to read text accurately and quickly

- Vocabulary: the knowledge of words necessary to communicate effectively

- Comprehension: the ability to understand and gain meaning from what has been read

At the heart of its work, the National Reading Panel’s recommendations were fairly simple. Teachers should be using best practice and what is proven effective – according to scientific data and not focus groups – to teach young people to read. We should do what works. We should do what we know is best for kids, particularly for those who struggle with reading proficiency.

Unable to win against the research, whole language programs decided to rebrand themselves. Rather than embrace the data, many re-wrapped failed programs as “balanced literacy.” There was nothing new in the approach. Balanced literacy advocates continued to attack scientifically proven methods as “drill and kill” and still advocated that whole word memorization and proximity to children’s literature remained the secret to success. Phonemic awareness, phonics, and fluency still weren’t necessary to build strong, confident readers, regardless of what the science has said, says, and will continue to say.

So it is worth noting when Lucy Calkins quietly releases “Postcards from a Journey: Rough Draft Insights from the Science of Reading Discussion,” three pages of bullet points that proclaim, for those without their doctorates, “oops, our program doesn’t really work like we’ve said it did for nearly a half century. Our bad.”

Calkins now declares that phonemic awareness “is a foundational component of reading success.” That “it’s cause for concern when children who receive appropriate instruction are slow to develop it.” That scientifically based reading approaches used with students with dyslexia “also benefit typically developing students.” And that students benefit from a phonics-based approach to texts, and that “all children can benefit from opportunities to read carefully selected decodable tests in the early stages of reading.”

To that, all we can say is, “we told you so.”

Too many years have been spent, too many dollars wasted, with too many students falling and remaining between the cracks because too many were unwilling to acknowledge what Calkins has finally admitted to. Scientifically based reading instruction works. If we want virtually all fourth graders to be reading at grade level (an essential metric in the teaching and learning process), then we need to provide them with a proven approach to literacy rooted in phonics, phonemic awareness, fluency, vocabulary, and reading comprehension.

No, we don’t need to rebalance balanced literacy. Whole language was discredited because it didn’t work. It was a philosophy, an approach, to literacy that lacked a proven curriculum that actually taught kids to read. Rebranding it as balanced literacy may have ensured sales and boosted the number of school districts enrolling their teachers in workshops, but it has similarly done nothing to teach kids to read. Balanced literacy needs to be cast aside, not rebalanced.

With all we know about research and cognitive science, with all of the data we now hold on effective teaching and learning, with what we know about learning disabilities and English language learning, it borders on educational malpractice if we are focusing classroom instruction on approaches that lack evidence. Too much is at stake – for both our learners and our society – to waste our time and instructional dollars on snake oil and well-intentioned, yet unsuccessful, philosophies or beliefs.

We can do nothing for the generations of struggling readers that we failed because we gave them balanced literacy instead of research-proven reading instruction. But we can ensure that today’s youngest learners, as well as future generations of students, gain the literacy skills they need. That only comes from strong, consistent exposure to the most effective instructional approaches available.

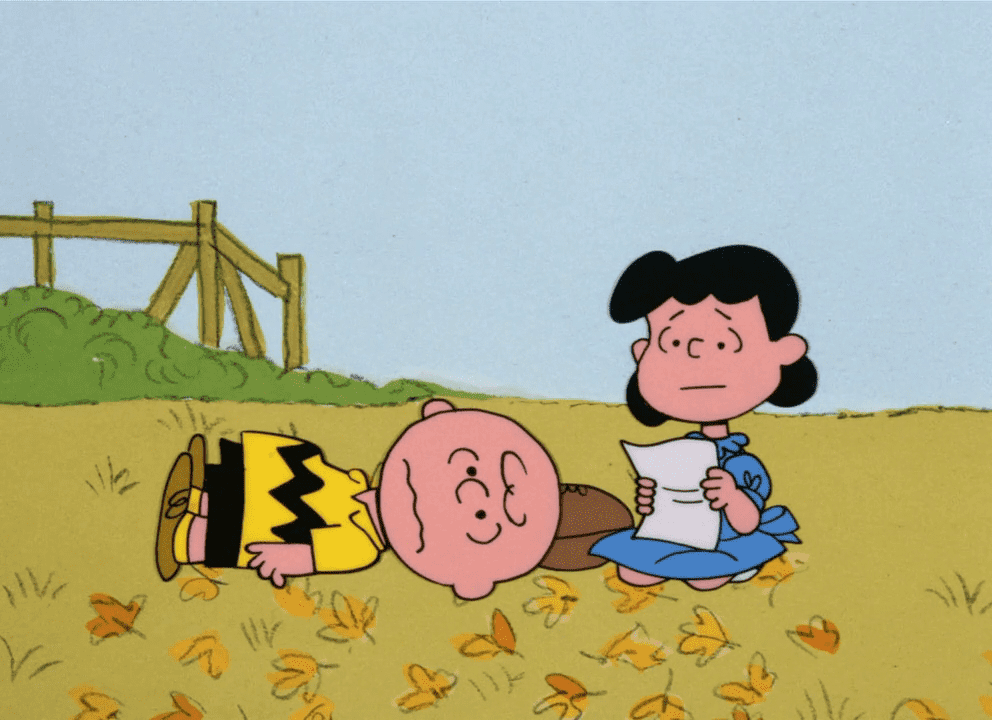

Those who know are all too aware of how many times Lucy pulled the football away from Charlie Brown, promising him that the next time would be the time she lets him kick the ball. For generations, whole language advocates have been pulling the ball away, promising the next time would be the time when we really start teaching kids to read. At some point, Charlie Brown needs to take responsibility for letting him be fooled, time and again. That’s where we are with reading instruction today. Promises to rebalance balanced literacy are nothing more than one more yank of the football, as aspiring readers land on their backs. If we are going to kick the literacy football, we need to scientifically based reading on our team.