Online Learning Is Failing My Kids

“I really like paper and pencils,” my son recently told his fourth grade teacher during a Zoom call.

He’d asked if he could complete a math worksheet on paper rather than on the computer. Instead of providing a printable worksheet, the teacher offered to guide him through the online process. I was too tired to argue.

Kids Love Screens

I have three sons. As with most kids their ages, they love screens. Any screen-based entertainment will do–television shows, games, YouTube, movies. Like most parents, I struggle to limit their access. Even outside of a global pandemic, when my kids could roam wild in the neighborhood or wander over, allowance in hand, to the local ice cream or pizza shop, I would still set strict limits on screen and game time. I set passwords for YouTube and other television channels, games are only permitted on weekends with limited hours, and no games allowed on weekdays unless it’s a holiday. Most of my children’s friends live under similar rules, so I don’t face the problem of them having too much screen time at friends’ houses.

Yet, I do face tremendous competition at their schools where my children spend hours on computers and where there are inconsistent rules about screen time.

In some ways, it’s like sharing custody with an ex who doesn’t share my parenting philosophy. It’s a very difficult landscape to navigate as a parent, and worse, it leaves children vulnerable to mixed messages and confusion about what’s right and wrong and who is the real authority on the issue.

Online Learning Earlier Than Ever

Today, computers in classrooms are the norm. According to Larry Cuban, a professor emeritus at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Education, laptops began appearing in classrooms in the mid-1990s as they became more ubiquitous and affordable. Tech companies soon realized the potential and began to push to have electronics in classrooms—even providing them for free to some underprivileged areas.

Google, Apple, Microsoft and others are competing not just to be a classroom tool, but to shape what is being taught. A 2017 New York Times report described Google’s growing role: “Google is helping to drive a philosophical change in public education — prioritizing training children in skills like teamwork and problem-solving while de-emphasizing the teaching of traditional academic knowledge, like math formulas. It puts Google, and the tech economy, at the center of one of the great debates that has raged in American education for more than a century: whether the purpose of public schools is to turn out knowledgeable citizens or skilled workers.”

And so, Google Chromebooks and other laptops are now a regular part of learning—even in elementary school where, as the name signifies, the learning covers elementary subjects that don’t require high tech tools.

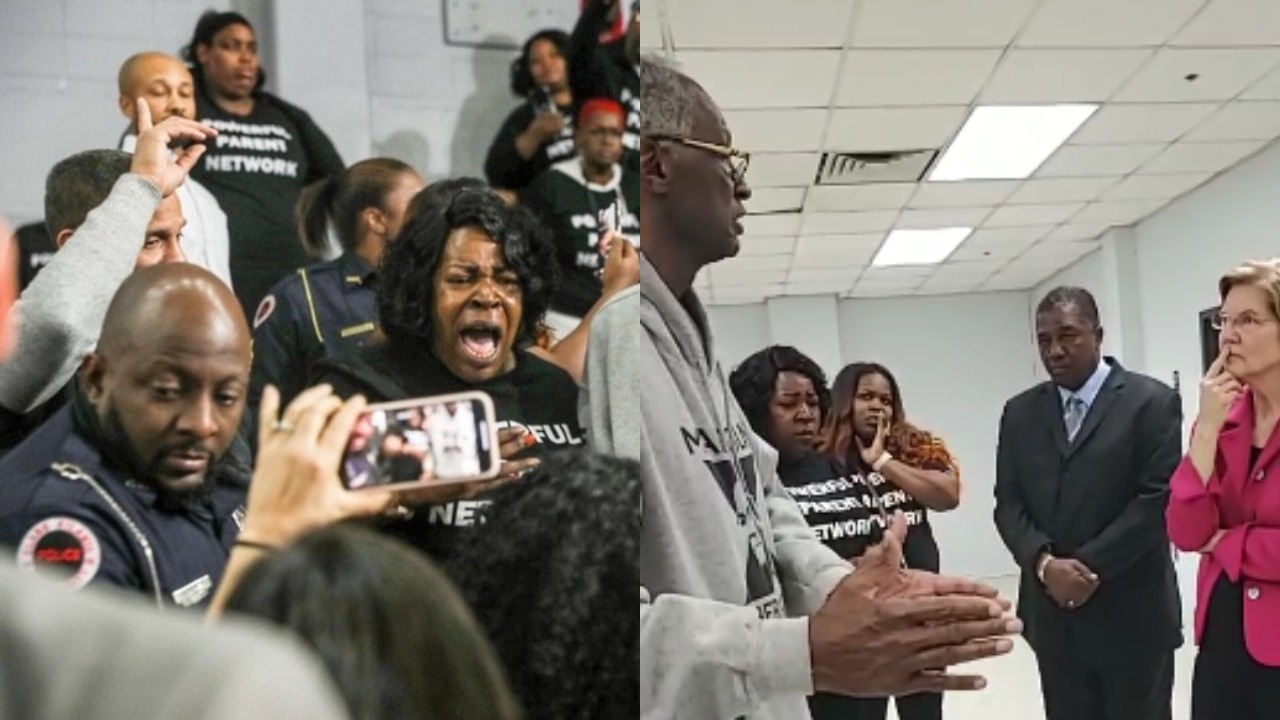

Of course, online learning isn’t all bad. Some charter schools are entirely virtual and some students do better learning this way. Yet, with these types of schools, the student and parent have likely chosen that model of education because it’s best for them.

According to Common Sense Media, eight-to 12-year-old kids spend just under 5 hours a day on some sort of screen and teens are on them for about seven and a half hours. Sadly, that does not including use of screens at school or after school for homework. While some parents I’ve spoken to defend online learning by saying they want their kid to be tech savvy as early as possible, most parents are worried. A Pew Research Center survey showed 65 percent of parents say their kids spend too much time online. Interestingly, 54 percent of teens agree.

This ubiquity of computer devices has a cost—it’s created barriers to parents understanding how their children are learning and even faring in school.

Take my youngest son, who was issued a computer in third grade (he was 8!). Soon after, I noticed fewer graded worksheets coming home. I missed those smiley faces, bright gold stars, and silly stickers he’d always show me, beaming with pride.

Even art projects dwindled. While my child was still receiving teacher guidance and instruction during classroom time, the workload was almost entirely computer based—from in-class work to tests. And homework was also falling off. In fact, I had to request (multiple times) that my child receive paper worksheets to do at home.

When graded worksheets declined, I lost a sense of how my child was doing in the classroom. The only real indication of his progress and performance was at the once-a-quarter, 15-minutes parent-teacher meeting and quarterly report cards.

Yet, even report cards have changed. My mother kept several of my report cards from the 70s and 80s, which gave my parents a unique peek not only into my personality (she’s got one!), but my challenges focusing (she has trouble sitting still) and my disruptive tendencies (she can’t stop talking to her peers). My report cards also included lengthy and very specific teacher-written notes about my likes and dislikes, my productivity, and what the teacher viewed as my strengths and weaknesses.

Sadly, I don’t get that sort of granularity about my own child’s performance in the classroom. Instead, I get canned comments that revolve around what was taught (“this quarter, we learned about Jamestown”), instead of how and if he’s absorbing or understanding the content. There are a few “he’s a curious kid” and “I’ve enjoyed teaching him” bromides thrown in there, but that’s the sort of nonspecific information that does nothing to help a parent understand a child’s educational needs and direction.

Lockdown Learning and Locked-Out Parents

Now, with schools in lockdown and parents turned into ersatz teachers, schools have become even more reliant on the online model of teaching. This creates a curious dynamic: While parents are needed more than ever to help their kid stay on course and meet deadlines, the online format (at least the one used by my school district—which I suspect is no different than most) can’t be accessed by parents.

In order to see what a child is doing, parents have to use the child’s computer and familiarize themselves with the various educational platforms (designed for schools) that are used by students. It’s a steep, sometimes impossible learning curve. And because assignments are turned in via the computer, parents aren’t always aware of when or if their child has completed an assignment.

Of course, this isn’t some wicked system created by teachers to keep parents at arms length. Rather, it’s just the natural byproduct of a system designed for children and teachers who are using the same system. I do receive some automated messages, yet they don’t contain any detailed information or provide any guidance or instructions that would help us aid our son. And of course, we can’t respond back to these notifications.

In the physical classroom, my son would be able to get this sort of assistance and feedback. He need only raise his hand to ask. But to do that under this online learning regime, my son has to attend a zoom meeting during the teacher’s once-a-week office hours and ask the question then. That is, if he remembers.

Leaving parents out of these online platforms makes solving these problems needlessly hard. After my son started missing Zoom meetings with his teachers, my husband attempted to create a joint calendar so that we, along with our child, could be jointly alerted about meetings. This would help us—distracted with our own work—keep our son on task and remind him of upcoming meetings.

But sadly, my son’s Chromebook doesn’t accept outside calendar invites, nor can we email him on his school email address. This is obviously for security reasons, and we appreciate that feature, but it creates a wall between student and parents that wouldn’t exist in a low-tech system. And this wall is especially problematic when parents are really the only adults available to help kids with schoolwork.

It has now been about 8 weeks post Spring Break. My kids are learning entirely with online platforms and are spending roughly five to six hours per day on their computers (with breaks built in by me). Tasks include watching BrainPop videos, watching instruction videos from teachers, attending live Zoom instructional meetings with teachers, attending zoom office hours with teachers to ask questions about assignments, as well as doing nearly all schoolwork in an online format—involving computer-based questions.

And there are all sorts of different programs—Clever, Think Thru Math and Imagine Math, Ed Puzzle, SeeSaw, Google Classroom, SOL Pass, BrainPop, Canvas, Google Docs, Epic, Gmail, Discovery Education. Sometimes one assignment involves multiple platforms. One must be a master of all.

Some may read this and think, “Well, that lady is just really bad at technology.” That might be true. But I actually live with an IT executive who is also having trouble figuring out how these platforms work. The problem isn’t the individual platform; it’s the fact that there are so many.

Parents Should (and Can!) Have Low Tech Options

Each week, I receive a variety of “check in” messages from school personnel. There are weekly news updates, academic checklists, notes about the yearbook, school lunch pick-up locations, notices of cancelled graduation ceremonies, and other housekeeping matters. All sent to me from the school via email. This already existing, direct school-to-parent communication system is designed to keep parents informed but it could also be used to provide parents low-tech instructional materials that can be printed at home. At the very least, it should be an option for parents.

Of course, as the world becomes increasingly paperless, printers aren’t as ubiquitous in homes as they once were. Anecdotally, I see this problem myself as I’m often asked to print off shipping labels for (not poor) friends and neighbors who don’t own printers. Yet, there’s another direct school to parent system that can solve this printing problem.

In my town of approximately 150,000 people, the school district is providing all public school students and children over the age of two the option to pick up what’s called Grab-And-Go breakfasts, lunches, and what they call “snack meals” on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. These meals are distributed at five separate school locations as well as eight other “pop up” locations (this includes some large-scale apartment complexes and community centers). There is no sign-up necessary nor is a registration required to receive meals. And thanks to a waiver from the USDA, kids do not need to be present for a parent to pick up a meal or meals.

Considering this infrastructure that already exists, why not use this same distribution system to offer paper-based educational packets to parents, who might want low-tech options. Parents who do not own a computer or printer, could simply go to a distribution site to pick up a week’s worth of paper-based worksheets and educational materials that have been curated by teachers and is consistent with the class curriculum. Online learning could still be a part of the broader learning experience and teachers could still use online resources to connect with kids and conduct distance instruction. But parents would have the option to go low tech if they wanted to keep their kids away from screens a bit more.

I know this system can work because it was already done in the elementary school that two of my kids attend.

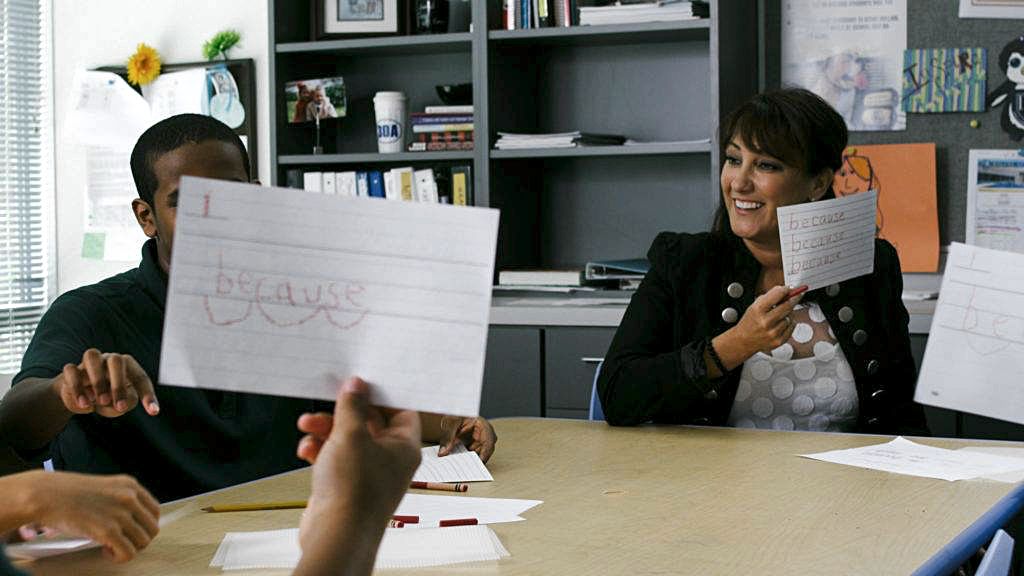

On the last day before the school closure, my two younger children each arrived home with a school-provided packet of worksheets, reading materials, and other written assignments. There were math and writing problems, science questions, history assignments and even music sheets so that they could continue to practice their bass and violin. There was even a calendar that listed topics to prompt them to free write each day in a notebook. My youngest son particularly enjoyed the free writing—which while crafted as a school assignment, wasn’t overly prescriptive, so allowed him to be creative.

My youngest particularly enjoyed the grading part of the day where he would bring me his worksheets and I would grade them using a big, fat green marker—being sure to add smiley faces and hearts when he did particularly well. I used a thin red marker to put an X next to problems he needed to redo. He’d dutifully run back to his table, complete the problem and hand it back to me, eagerly waiting for that fat green checkmark. I reported this back to his teachers via email, explaining that he was completing his work and doing good on his problems.

A few weeks later, we’d run out of paper-based materials and the school switched to an entirely online system. No more worksheets. No more big, fat, green marker.

Parents Deserve Options

To employ an overused phrase: recent events have been unchartered territory for schools. When the stay-at-home orders were announced, schools had to move quickly to develop a system for teaching kids from home. It’s understandable that mistakes were made and that adjustments need to be made going forward.

Over the summer break, schools need to figure out better ways to communicate with parents. And they need to give parents better access to school-based learning systems and more choices in how kids learn. Low tech options are a relatively easy thing to provide parents. It doesn’t involve Wi-Fi hotspots, Chromebooks purchases, video instructions, or zoom calls. It’s as simple as providing kids a paper worksheet.

Parents can throw in the pencil.