Redlining: The Real Reason Our Schools Are Segregated

In the aftermath of the George Floyd murder, many protesters have focused on systemic racism and the ways that our social compact has failed lower-income Americans and people of color. One of the most obvious failures is our public school system, which remains starkly unequal and divided along racial and economic lines. This is 66 years after the Supreme Court outlawed segregation in the Brown v. Board of Education case, famously requiring that the public schools must be “available to all on equal terms.”

So whyare our schools still segregated? Many education writers have a stock answer to this question. It is school choice, they say, that is responsible for the segregation of our schools. The only problem with this stock answer is that it isn’t true.

Take the opinion piece “School Choice Is the Enemy of Justice” by Erin Aubry Kaplan in the New York Times: “Black and brown students have more or less resegregated within charters, the very institutions that promised to equalize education.”

Or look at the academic white paper produced by the UCLA Civil Rights Project, Choice without Equity: Charter School Segregation and the Need for Civil Rights Standards:

As the country moves steadily toward greater segregation and inequality of education for students of color in schools with lower achievement and graduation rates, the rapid growth of charter schools has been expanding a sector that is even more segregated than the public schools.

It sounds damning, doesn’t it?

But here is the truth: 78% of public school children attend their assigned public school. If American public schools are divided along economic and racial lines (and it’s indisputable that they are), then it is primarily because of school assignment policies, not because a minority of parents look for better public school options for their children.

And how are children assigned to schools? By their address. Our public schools are segregated because of the lines that are drawn, showing who gets into good public schools and who gets kept out. These lines often exclude many middle-class and lower-income families, especially immigrants and minorities.

Take a look, for example, at two schools that serve families in the Old Town neighborhood of Chicago. At Lincoln Elementary School only 16% of the students at Lincoln come from low-income families, and over 80% are proficient in reading. The school shares an attendance zone boundary with Manierre Elementary school, where 99% of the students are low-income, and only 11% are proficient in reading. These two schools, so starkly different, serve the same neighborhood.

For almost a mile of North Avenue in Chicago, a child on one side of the street is guaranteed access to Lincoln Elementary, one of the shining stars of the Chicago Public Schools, while a child on the other side of the street is turned away and assigned to failing Manierre. There’s no way to avoid the racial implications of this: Lincoln has over 60% white students, and CPS reports that Manierre had 0% white students in 2019.

This is not unique to Chicago. Look at PS 8 Robert Fulton in Brooklyn. Or Ivanhoe Elementary and Mount Washington Elementary in Los Angeles. Mary Lin Elementary in Atlanta. Lakewood Elementary in Dallas. Peralta Elementary in Oakland. John Hay Elementary in Seattle. Penn Alexander School in Philadelphia. And many, many more.

The pattern is the same: State law allows (or even requires) the district to draw attendance zones showing who gets to attend which schools. Districts use the lines to determine who can enroll in these elite, high-performing public schools. Young families respond to the policies by cramming into the coveted zone, driving up home prices. Other parents lie about their address to gain access. The divide between the two schools, often just blocks apart, grows over time.

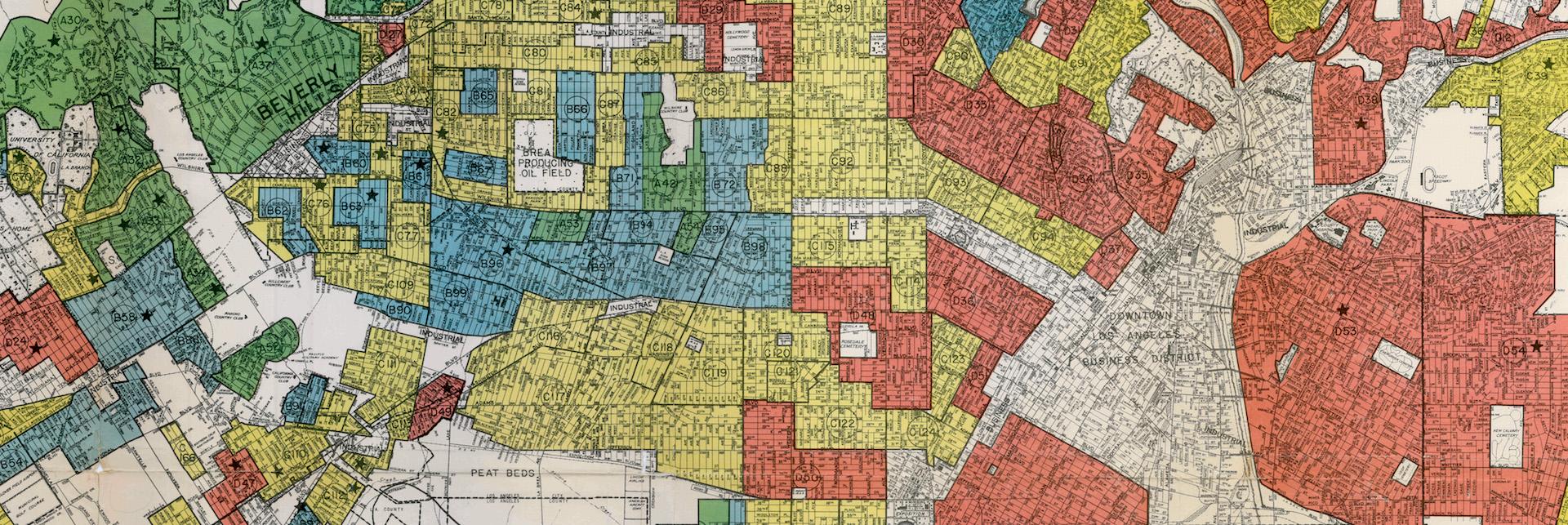

We already have a name for this practice of using your address to determine whether or not you are eligible for valuable government services. We call it redlining. The name comes from government maps created during the New Deal. These maps used the color red to indicate those urban neighborhoods that were “hazardous,” which mostly meant that those areas were majority black or Hispanic. People in these red-shaded portions of the map were ineligible to qualify for some federally subsidized mortgages.

As a part of the research for my new book on attendance zones, we compared the attendance zone maps for these elite public schools with the racist redlining maps of the 1930s. What we found will astound you. In many cases, the shape of the attendance zone still mirrors the shape of the “desirable” areas from the 1930s—and still excludes those portions of the neighborhood that have higher concentrations of minorities and immigrants. See how this plays out at Ivanhoe Elementary in Los Angeles:

In my book, I also point out that many of these elite public schools have attendance zones that are in clear violation of a federal civil rights law from 1974. As I have written in the journal Education Next, the Equal Educational Opportunities Act prohibits a district from assigning a minority student to a school that is not the nearest to his or her home, if it will enhance segregation. The law was passed precisely because Congress knew that school districts could use the zone lines as a way to create protected public schools that would appeal to upper-middle-class white constituents.

Many minority families who are assigned to struggling or failing schools may be surprised to learn that they have—under federal law—the right to an equal opportunity to enroll in the coveted public school in their neighborhood, if that school is the closest to their home. The animation below shows how this law works and the protections that it provides for minority families:

The New York Times and the UCLA Civil Rights project, as well as many other education experts and journalists, would like you to blame school segregation on those Old Town parents who seek out a better option for their children, rather than leaving their kids in a failing public school like Manierre. But that doesn’t make any sense. If those families were obedient and did what the government told them to do, then their children would be in a hyper-segregated failing school.

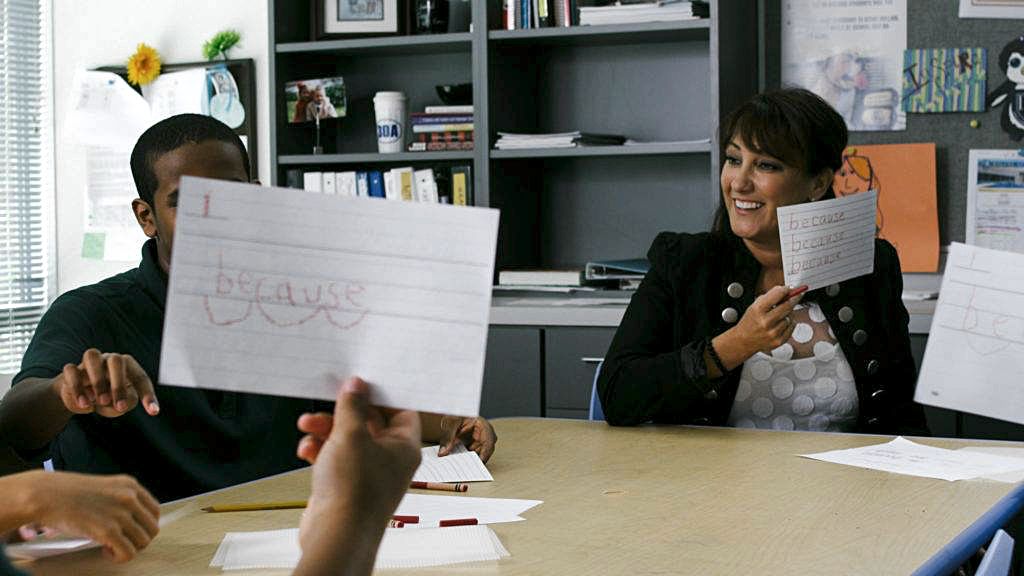

Here’s the reason that charter schools have high concentrations of lower-income children of color: Those families have been disproportionately assigned to failing public schools, so they are the ones who are most eager to take advantage of laws that allow them to find other options.

If we are going to begin to break down the racial and social divisions in our urban schools, we need to abolish attendance zones and provide every family an equal opportunity to enroll in the best public schools.