Time for Democrats to Recognize the Progressive Roots of Charter Schools

Listening to the rhetoric of Democratic presidential candidates, one would think charter schools were a Republican initiative opposed by all progressives. Bernie Sanders calls for a halt to all federal funding for charter schools. Elizabeth Warren joins him in condemning for-profit charters.

Former Vice President Joe Biden, who served under a president enthusiastic about charters, told the American Federation of Teachers at a forum, “The bottom line is it [chartering] siphons off money for our public schools, which are already in enough trouble.”

Even candidates who have been charter supporters in the past, such as Michael Bennet, Beto O’Rourke, and Julian Castro, have had nothing positive to say about charters. All seem afraid to draw the ire of the teachers’ unions, which contributed $64 million to candidates, party organizations, and outside spending groups during the 2016 election, according to the campaign finance tracking organization, OpenSecrets.

So it may come as a surprise to readers that chartering originated as a Democratic initiative. Democrats spearheaded charter legislation in most of the early charter states, and Democratic Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama enthusiastically supported charters, pushing through federal legislation to provide funding.

The innovative Democrats who pioneered chartering were looking for a better organizational model for public education — a system designed for the Information Age rather than the Industrial Era. In their new approach, an “authorizer” — usually the state or local school board — grants performance contracts to groups of individuals or nonprofit organizations that apply to open new public schools. Exempt from many of the rules that constrain district-operated schools, they are encouraged to innovate, to create new learning models that will appeal to children bored or otherwise dissatisfied with traditional schools. If a school succeeds, its contract is renewed; if it fails, it is closed. Families can choose between a variety of schools. Districts lose their monopolies on taxpayer-funded education, and their schools can no longer fail students for generations; the competition either takes away their students or forces them to improve.

The new schools are called “charter schools” because their performance contract is a charter. Over the past two decades, cities that have embraced chartering, such as New Orleans, Washington, D.C., Denver, Newark, and Indianapolis, have experienced profound student growth and school improvement. The charter formula — school-level autonomy, accountability for results, diversity of school designs, parental choice, and competition between schools — is far more effective than the centralized, bureaucratic approach that developed more than a century ago.

Teachers at charter schools tend not to unionize, however, so as the charter sector grows, union membership shrinks. By 2000, union leaders and their allies had gone to war against charters. They claim that charters are a product of “corporate reformers,” a right-wing effort to “privatize” our public schools. These accusations are nonsense. More accurately, they are lies born of self-interest, designed to protect the jobs of mostly white, middle-class teachers and union officials at the expense of mostly poor, minority kids.

The Origins of the Charter Concept

In 1988, University of Massachusetts Education Professor Ray Budde, a former principal, published Education by Charter: Restructuring School Districts. He proposed that districts allow teams of teachers to “charter” a program within a school for three to five years.

The following July, Albert Shanker, then president of the American Federation of Teachers, expanded on the concept in his New York Times column, suggesting that teams of teachers charter whole schools, not just programs. Shanker believed that the U.S. needed school systems that provided educators with autonomy and “genuine accountability” for results. He urged school systems to charter schools with a variety of teaching approaches, so that “parents could choose which charter school to send their children to, thus fostering competition.”

In 1995, just two years before his death, Shanker told Republican Congressman Steve Gunderson, who was writing an education reform bill for Washington, D.C., that “every school should be a charter school.”

Democrats Lead the Way in Early Charter States

In 1988, after reading Shanker’s column, members of a nonpartisan civic organization in Minnesota called the Citizens League began working on a report that outlined the framework for charter legislation, led by former League Executive Director Ted Kolderie. In October, when Shanker spoke at the Minnesota Foundation’s annual Itasca Seminar, Democratic State Senator Ember Reichgott Junge and Democratic State Representative Ken Nelson were in the audience. Afterward, Reichgott Junge began drafting charter legislation, with Kolderie’s help, and in 1989 she and Nelson introduced the bill. It passed the Senate but failed in the House, two years running. Finally, in 1991, with help in the House from Democratic Rep. Becky Kelso, a compromise version finally passed. And in 1992, a group of veteran public school teachers opened City Academy in St. Paul, the nation’s first charter school.

In California, conservatives were preparing a voucher ballot initiative that would allow Californians to use tax dollars to send their children to any school they chose, public or private. Democratic State Senator Gary K. Hart, who understood that the electorate was deeply frustrated with public schools, decided the Democrats needed legislation to counter the voucher movement. Hart felt that vouchers relied too much on a free-market approach, threatening the equal opportunity that should be built into public education. A former teacher, he’d already sponsored a bill that gave 200 public schools more autonomy in exchange for more accountability. Chartering was the next logical step: a third way between vouchers and traditional systems.

Democratic Assemblywoman Delaine Eastin introduced a charter bill at the same time, but it required sign-off by the district’s collective bargaining unit for charter approval. Teachers unions pressured Hart to amend his bill to do the same, but he refused. He also stood his ground against demands related to parent involvement and teaching credentials. Hart believed such decisions should be left up to school founders and leaders. He wanted a simple bill that would create a system with limited bureaucracy, in which schools were judged on the basis of student outcomes, not compliance with rules.

Both bills passed the legislature, but Republican Governor Pete Wilson vetoed Eastin’s and signed Hart’s into law. The legislation took effect on January 1, 1993, and that fall, 44 charters opened.

The third bill passed in Colorado, where Democratic Governor Roy Romer was instrumental in pushing it through the legislature. In 1992, Republican Senator Bill Owens and Republican State Representative John James Irwin introduced a bill to create a new, independent school district to authorize and oversee “self-governing” schools. That bill died in the Senate Education Committee, whose chairman, Republican Senator Al Meiklejohn, stood firmly against choice and charters.

Irwin died before the 1993 session, so Owens and his allies reached out to Democratic State Representative Peggy Kerns, to sponsor a new charter bill in the House. The unions and other establishment groups opposed the bill, and Meiklejohn neutered it with amendments in the Senate.

In the House, Kerns and fellow Democrat Peggy Reeves re-amended the Senate bill so that it more closely resembled the original. Gov. Romer met with the Democratic caucus and rallied support on the House floor. The bill narrowly passed, the two bills were reconciled in conference committee, and both houses passed the new version. On June 3, 1993, Romer signed the Charter Schools Act into law.

In Massachusetts, Democratic State Senator Thomas Birmingham and Democratic State Representative Mark Roosevelt, then co-chairs of the Joint Committee on Education, spent several years developing the 1993 Massachusetts Education Reform Act, which sought to reform the state’s education financing system while increasing academic expectations and school accountability.

In the fall of 1991, a mutual friend introduced Roosevelt to David Osborne, who had recently finished a new book, Reinventing Government. Roosevelt described for Osborne the higher academic standards he planned to include in the legislation. Osborne said, “That’s great; standards are important. But what are you doing to do when districts don’t meet them?”

Roosevelt explained that the state would take over underperforming districts. Osborne pointed out that takeovers would stir up intense resistance, severely limiting their use. You need another strategy, Osborne told him. You need choice and competition.

Shortly afterwards, he introduced Roosevelt and his staff to the concept of charter schools. A few weeks later, when Ted Kolderie told Osborne he was planning a trip to Boston, Osborne put him in touch with Roosevelt, and Kolderie helped Roosevelt and his staff write charter language for the bill. When the teachers unions came out against the charter proposal, Roosevelt and Birmingham introduced a cap on the number of charter schools, as a compromise.

In 2016, Roosevelt and Birmingham urged Massachusetts to raise its cap: “We included charter public schools in the 1993 law to provide poor parents with the type of educational choice that wealthy parents have always enjoyed…. We now have enough data to conclude that charter schools have exceeded expectations. In our cities, public charter schools consistently close achievement gaps. No wonder more than 32,000 children are on charter school waiting lists. Imagine being one of the parents crushed with disappointment when your child is not selected.”

By the end of 1994, seven more states had enacted charter laws. Democrats spearheaded the legislation in Georgia, Hawaii, and New Mexico, Republicans in Arizona and Wisconsin, and there was overwhelming bipartisan support in Michigan and Kansas. Of the next 23 states, which passed bills in the rest of the ’90s, all but three had strong bipartisan support.

Even today, most education reformers are Democrats. A study by the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) showed that 87 percent or more of the political contributions made by staff at education reform organizations over the past decade went to Democratic candidates. “The leading participants in the school-reform ‘wars’ are mostly engaged in an intramural brawl,” the authors concluded, “one between union-allied Democrats and a strand of progressive Democrats more intent on changing school systems.”

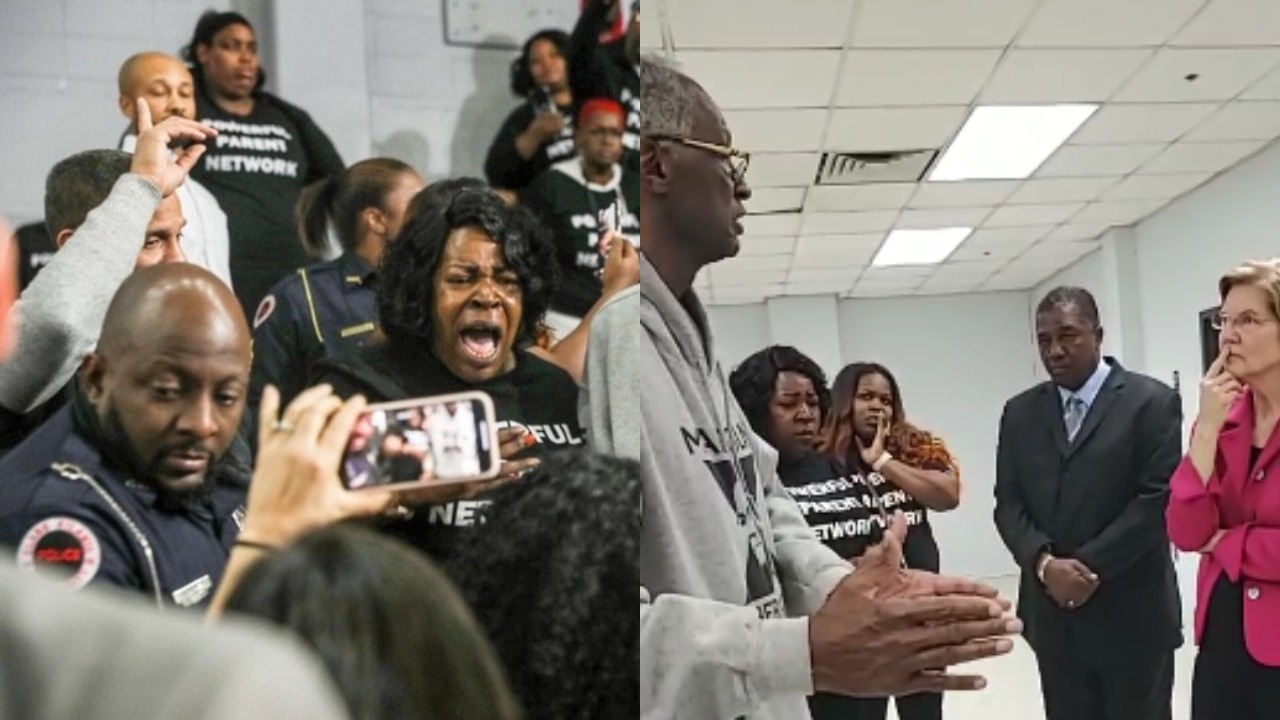

As reform-minded Democrats attempt to put children first, union-backed Democrats block them. They betray America’s children — particularly those whose parents lack the money to move into a district with strong public schools or send their children to private schools.

Voters should ask this year’s presidential candidates: Which type of Democrat are you?

David Osborne, author of Reinventing America’s Schools: Creating a 21st Century Education System, leads the education work of the Progressive Policy Institute. Emily Langhorne, a former associate director of that project, is now at DAI, which works on economic and social development in low-income countries around the world.

This post originally appeared on Medium as “The Progressive Roots of Charter Schools.“